Let me share just some of the things that she said that made me uncomfortable:

- If you have not devoted years of sustained study, struggle, and focus on racism, your opinions are limited and superficial.

- The status quo of our society is racism; it is the norm, and we are quite effective at reproducing it.

- We (white people - Dr. DiAngelo is white as well) see ourselves as unique individuals, unaffected by the culture we live in.

- Racism is a system, not an event.

- None of us are exempt from the anti-blackness in our culture and in our country.

- Smiling does not interrupt the system of racism.

- Niceness is not antiracism.

As she was speaking, and I was listening to these things, I was starting to feel more and more uncomfortable. So I began to make excuses and justify and rationalize what I was feeling. It's called "credentialing," according to Dr. DiAngelo. Here's what I was telling myself while she was speaking:

- I grew up in Mt. Vernon, NY; I had plenty of black students in my schools growing up.

- When I visited New York City, I saw plenty of black people.

- I played on of sports teams growing up that had black players.

- My first teaching job was in a school that was almost entirely full of black students.

In other words, those were some of my "credentials" that made it, so I was not a racist, and therefore I was immune to the discomfort I was feeling in the Davis Center on the campus of the University of Vermont that day. The truth is, I am not free from the patterns of racism, simply because of these experiences in my life.

The fact is, I've been benefitting from my race for as long as I've been alive, and even before that. As Dr. DiAngelo pointed out, my own mother benefitted from the prenatal care she had while she was pregnant with me in ways that black women in 1974 would not have had access to. I had teachers that were the same race as me beginning in kindergarten, and I saw the first teacher of a different race than me in seventh grade. I had only one black professor in my undergraduate education and no professors of a different race in graduate school.

And yet, I expect that the families of color in the St. Johnsbury School District will just entrust their precious children to me because the first time I was a teacher, I had a room full of black children? I must work to earn the trust of these families. I must struggle to be someone who shows, not just tells, the families of color that their children are in a building where we are aware of this inequity. I must work against the systemic, institutionalized racist structures in the second most white state in all of the United States.

Who will work with me? Who will stand next to me? Who will struggle with me?

Our students are waiting for those who will be allies. Who will ask the hard questions? Who will advocate? Who will step up?

Our students are waiting for our answers.

|

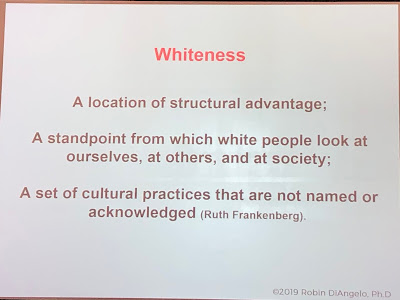

| Photo courtesy of Dr. Robin DiAngelo |